Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Why Investigate Moral Psychology?

Why moral pscyhology?

1

human sociality

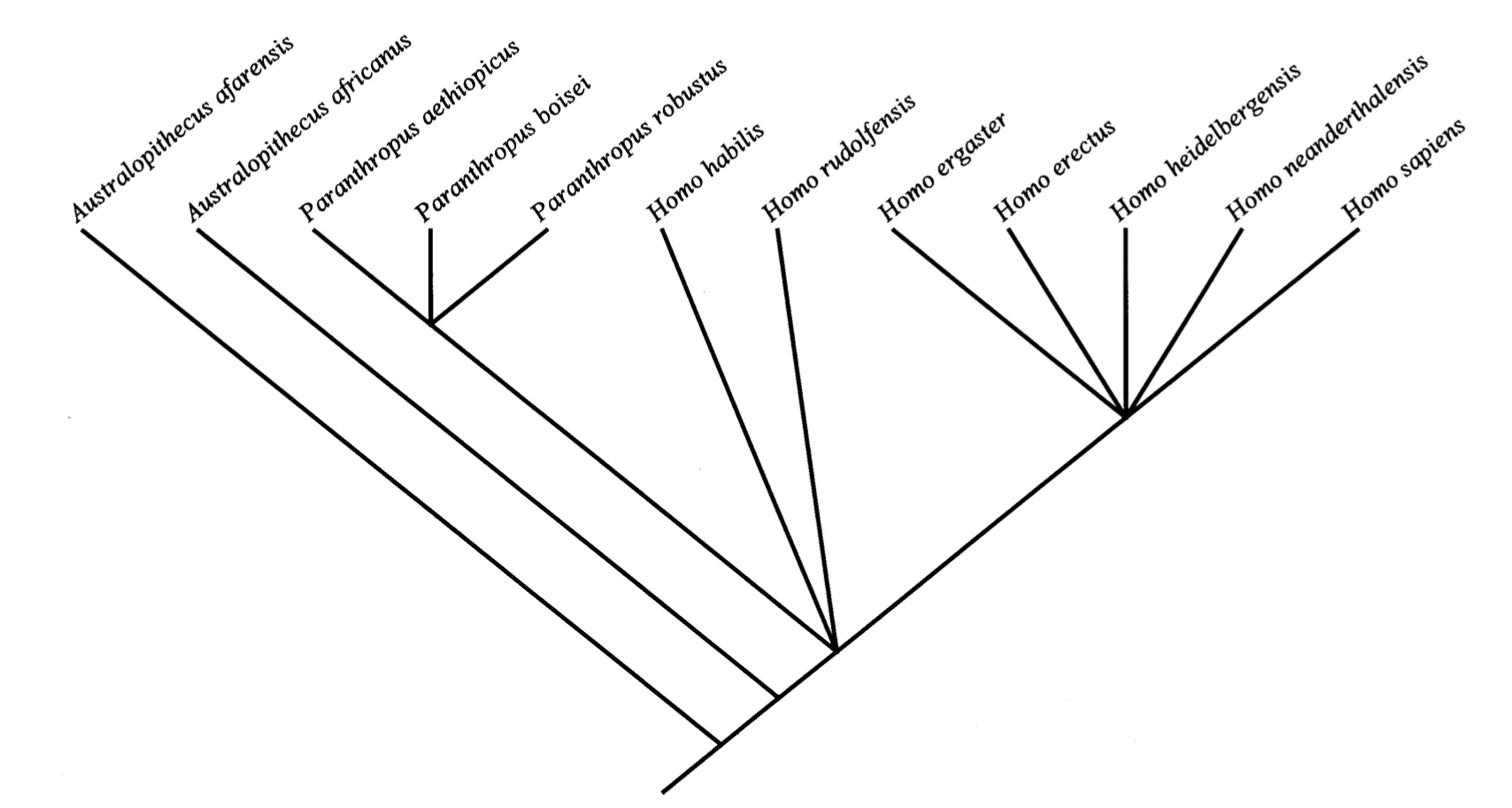

Modern humans

have recently (<10k years ago) begun to

live in societies roughly as complex as those of social insects

but cooperate with non-kin.

Why do humans do this?

obstacle: reciprocity and reputation are insufficient (e.g. Stibbard-Hawkes, Smith, & Apicella, 2022)

‘Humans are [...] adapted [...] to live in morally structured communities’ thanks in part to ‘the capacity to operate systems of moralistic punishment’ and susceptibility ‘to moral suasion’

Richerson and Boyd, 1999 p. 257

‘humans (both individually and as a species) develop morality because it is required for cooperative systems to flourish’

(Hamlin, 2015, p. 108)

rough hypothesis:

Ethical abilities explain,

in part at least,

why humans cooperate with non-kin

in ways that are adaptive.

1

human sociality

2

political conflict,

e.g. over climate change?

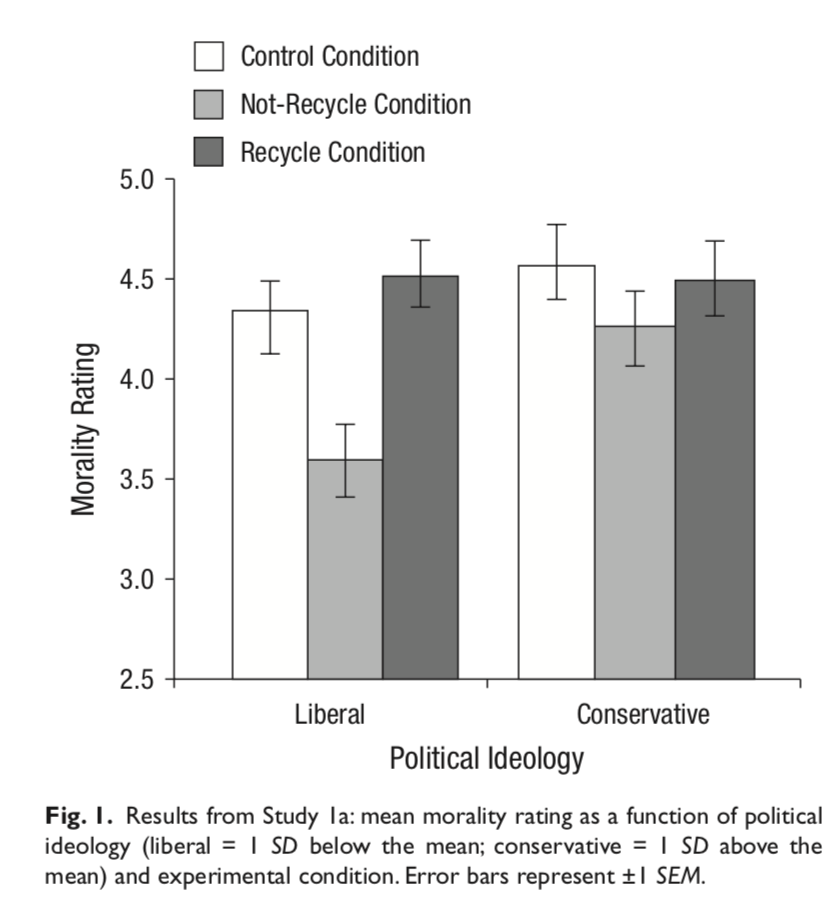

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 figure 1

Why are liberals generally more concerned about climate change than conservatives?

Why are liberals more likely than conservatives to regard climate change as an ethical issue?

‘intuitive ethics’ (Haidt & Joseph, 2004; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Atari et al., 2023)

harm/care

equality

proportionality

in-group loyalty

respect for authorty

purity, sanctity

Why are liberals generally more concerned about climate change than conservatives?

‘The moral framing of climate change has typically focused on only the first two values: harm to present and future generations and the unfairness of the distribution of burdens caused by climate change.

As a result, the justification for action on climate change holds less moral priority for conservatives than liberals’

Markowitz & Shariff, 2012 p. 244

2

political conflict,

e.g. over climate change?

3

ethics?

Could scientific discoveries undermine, or support, ethical principles?

‘Hier sehen wir nun die Philosophie in der Tat auf einen mißlichen Standpunkt gestellt [...]

Hier soll sie ihre Lauterkeit beweisen als Selbsthalterin ihrer Gesetze [...]

Alles also, was empirisch ist, ist als Zutat zum Princip der Sittlichkeit nicht allein dazu ganz untauglich, sondern der Lauterkeit der Sitten selbst höchst nachteilig [...]

Wider diese Nachlässigkeit oder gar niedrige Denkungsart in Aufsuchung des Princips unter empirischen Bewegursachen und Gesetzen kann man auch nicht zu viel und zu oft Warnungen ergehen lassen,

indem die menschliche Vernunft [...] gern [...] der Sittlichkeit einen aus Gliedern ganz verschiedener Abstammung zusammengeflickten Bastard unterschiebt, der allem ähnlich sieht [...], nur der Tugend nicht’

(Kant, 1870, p. AK 4:425--6)

Humans lack direct insight into moral properties

(Sinnott-Armstrong et al, 2010 p. 268).

Intuitions cannot be used to counterexample theories

(Sinnott-Armstrong et al, 2010 p. 269).

Intuitions are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations

(Greene, 2014 p. 715).

Philosophers, including Kant, do not use reason to figure out what is right or wrong, but ‘primarily to justify and organize their preexising intuitive conclusions’

(Greene, 2014 p. 718).

3

ethics?

!

personal

Why investigate moral psychology?

human sociality

political conflict

ethics

...

bonus idea: the gap