Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Against Reflective Equilibrium

Could scientific discoveries undermine, or support,

ethical principles?

Phase 2

Identify general arguments against the use of intuitions in doing ethics.

Consider implications for Rawl’s method of

reflective equilibrium.

Phase 1

Find places where a particular philosopher’s ethical argument relies on an empirical claim, and where knowledge of this claim depends on scientific discoveries.

✓

‘one may think of physical moral theory at first [...]

as the attempt to describe our moralperceptual capacity

[...]

what is required is

a formulation of a set of principles which,

when conjoined to our beliefs and knowledge of the circumstances,

would lead us to make these judgments with their supporting reasons

were we to apply these principles’

(Rawls, 1999, p. 41)

Background: How do philosophers do ethics?

‘Reflective equilibrium is the dominant method in moral and political philosophy’

(Knight, 2023)

‘this method, properly understood, is [...] the best way of making up one’s mind about moral matters [...]. Indeed, it is the only defensible method: apparent alternatives to it are illusory.’

(Scanlon, 2002, p. 149)

‘To most moral philosophers who reason about substantive moral issues, it seems that the method of reflective equilibrium, or a process very similar to it, is the best or most fruitful method of moral inquiry.

Of the known methods of inquiry, it is the one that seems most likely to lead to justified moral beliefs.

(McMahan, 2013, p. 111)

‘one may think of physical moral theory at first [...]

as the attempt to describe our moralperceptual capacity

[...]

what is required is

a formulation of a set of principles which,

when conjoined to our beliefs and knowledge of the circumstances,

would lead us to make these judgments with their supporting reasons

were we to apply these principles’

Rawls (1999, p. 41)

Could scientific discoveries undermine, or support,

ethical principles?

Phase 2

Identify general arguments against the use of intuitions in doing ethics.

Consider implications for Rawl’s method of

reflective equilibrium.

Phase 1

Find places where a particular philosopher’s ethical argument relies on an empirical claim, and where knowledge of this claim depends on scientific discoveries.

✓

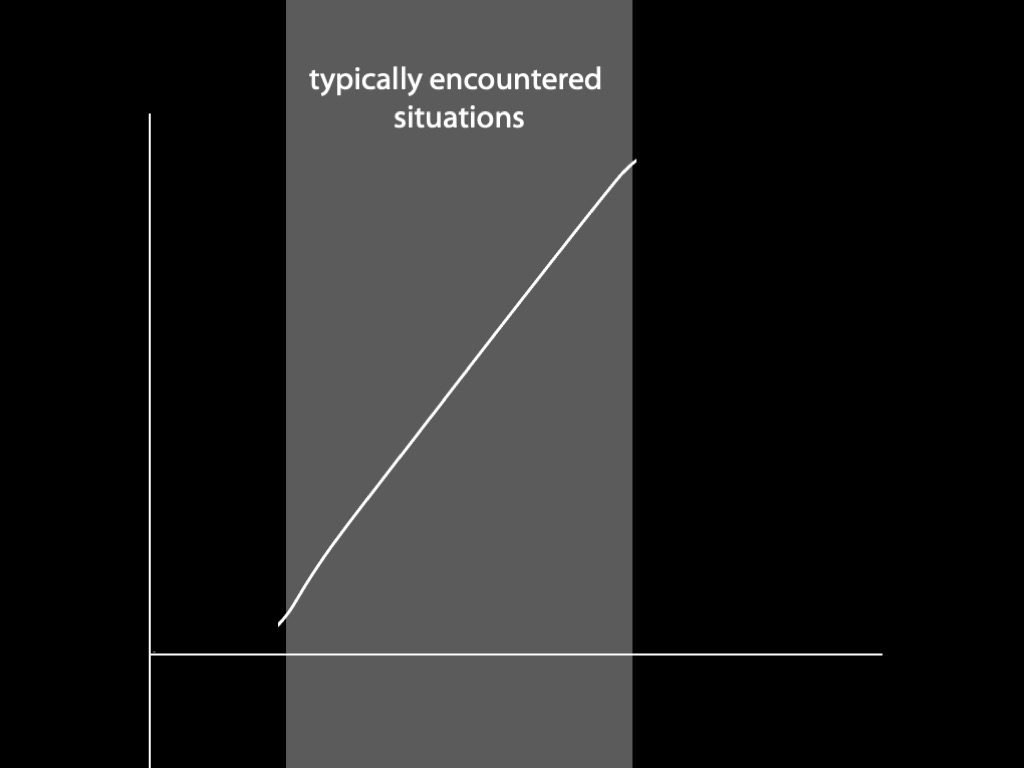

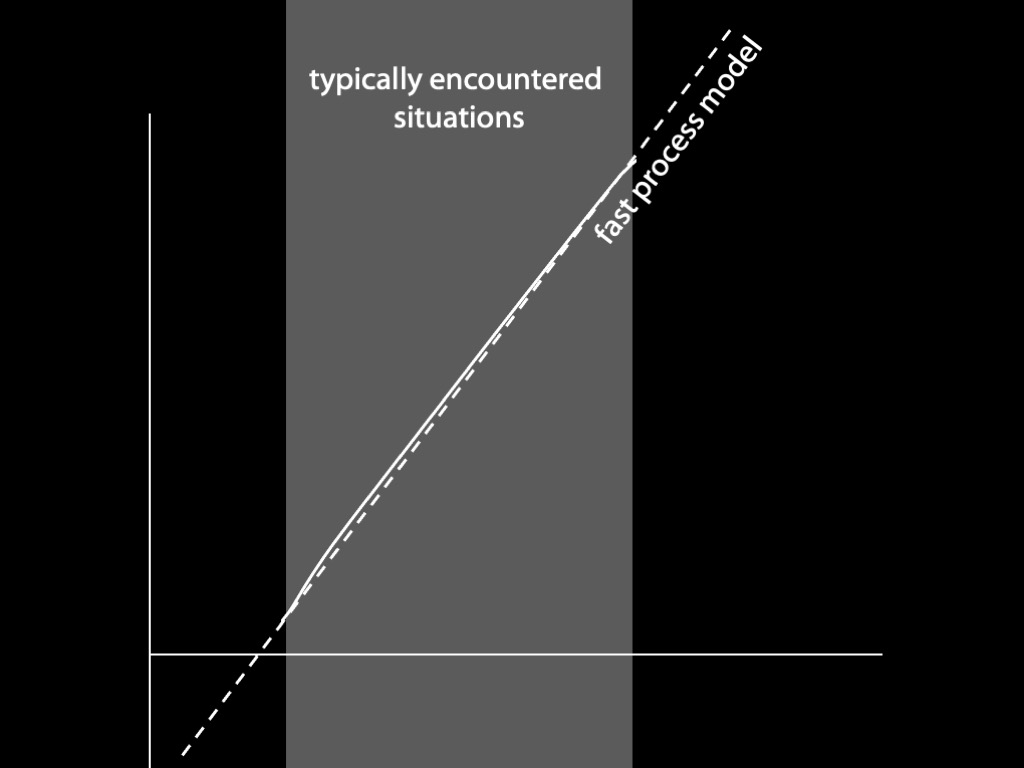

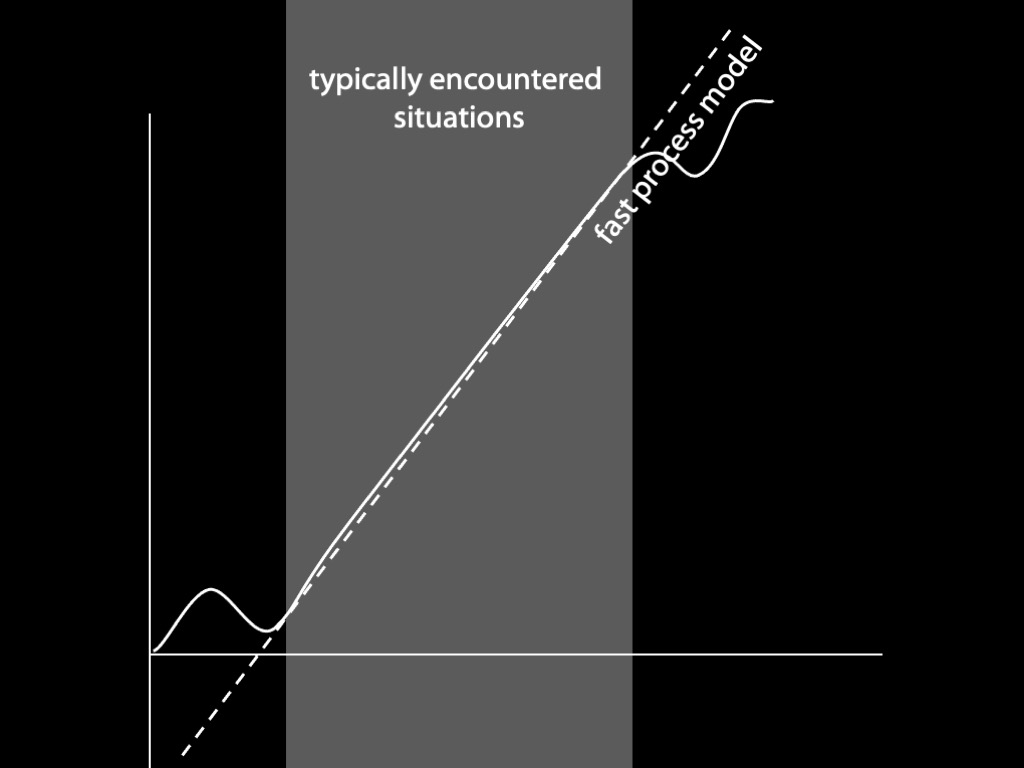

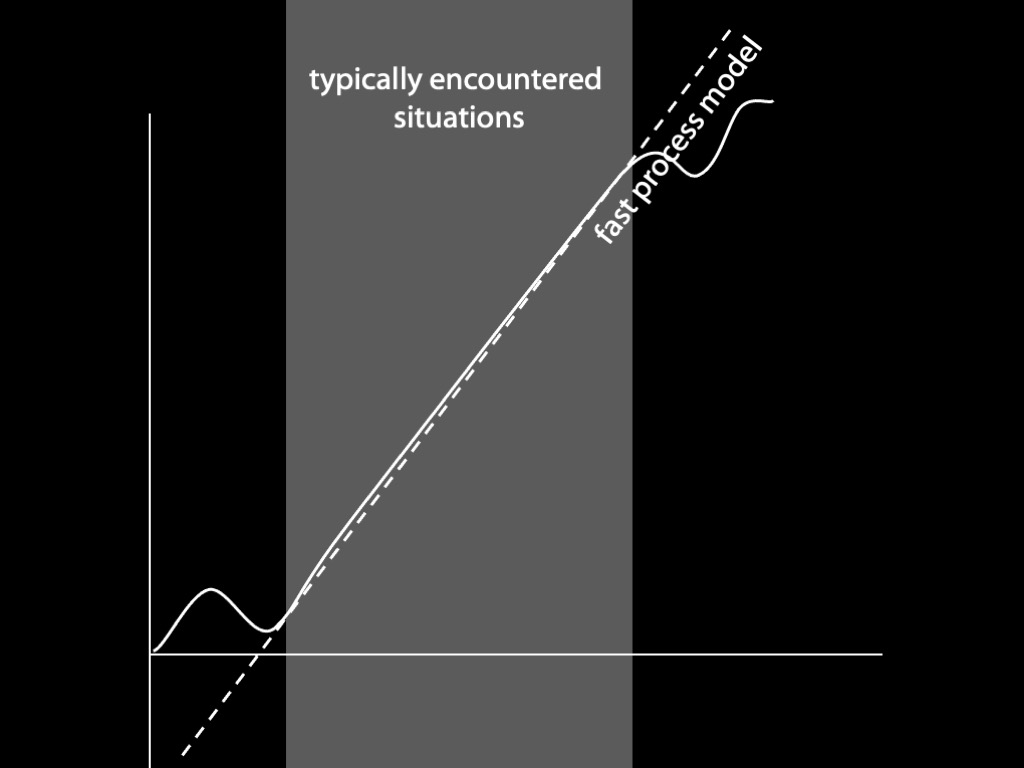

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. The moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

recall: speed vs accuracy trade-offs

wicked learning environments

‘When a person’s past experience is both representative of the situation relevant to the decision and supported by much valid feedback, trust the intuition; when it is not, be careful’

(Hogarth, 2010, p. 343).

dilemma

If your not-justified-inferentially judgements concerns only familiar situations, we don’t need it (we have the fast processes for that).

If your not-justified-inferentially judgements concerns unfamiliar situations, we have reason to reject it.

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. The moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

‘one may think of physical moral theory at first [...]

as the attempt to describe our moralperceptual capacity

[...]

what is required is

a formulation of a set of principles which,

when conjoined to our beliefs and knowledge of the circumstances,

would lead us to make these judgments with their supporting reasons

were we to apply these principles’

Rawls (1999, p. 41)

Dilemma for Rawls’ Reflective Equilibrium

Horn 1 : If you include not-justified-inferentially judgements about, or with implications for, unfamiliar* situations, you are not justified in starting there.

Horn 2 : If you include only not-justified-inferentially judgements about familiar* situations, you are not justified in generalising from them.

Not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

Reflective equilibrium ‘is [...] the best way of making up one’s mind about moral matters [...]. Indeed, it is the only defensible method: apparent alternatives to it are illusory.’

(Scanlon, 2002, p. 149)

But are you sure that ethical intuitions can be wrong?

‘a theory of justice is [...] a theory [...] setting out the principles governing our moral powers’

(Rawls, 1999, p. 44)

‘A useful comparison here is with the problem of describing the sense of grammaticalness that we have for the sentences of our native language. [footnote: Chomsky]’

(Rawls, 1999, p. 41)

Which comparison?

Ethics vs Physics

Not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

Extension to not-justified-inferentially premises generally?

‘debilitating pain is, other things equal, a bad thing, to be avoided or alleviated’ (Railton, 2014, p. 814)

Ethics vs Linguistics

Implies a form of infallibility.

Premises about judgements about particular moral scenarios need to be supported by carefully controlled experiments if they are to be used in ethical arguments where the aim is to establish knowledge of their conclusions.

But are you sure that ethical intuitions can be wrong?

And even if they can, does the loose reconstruction of Greene’s argument lead to a good objection to reflective equilibrium?