Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Evidence for Dual Process Theories

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. The moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

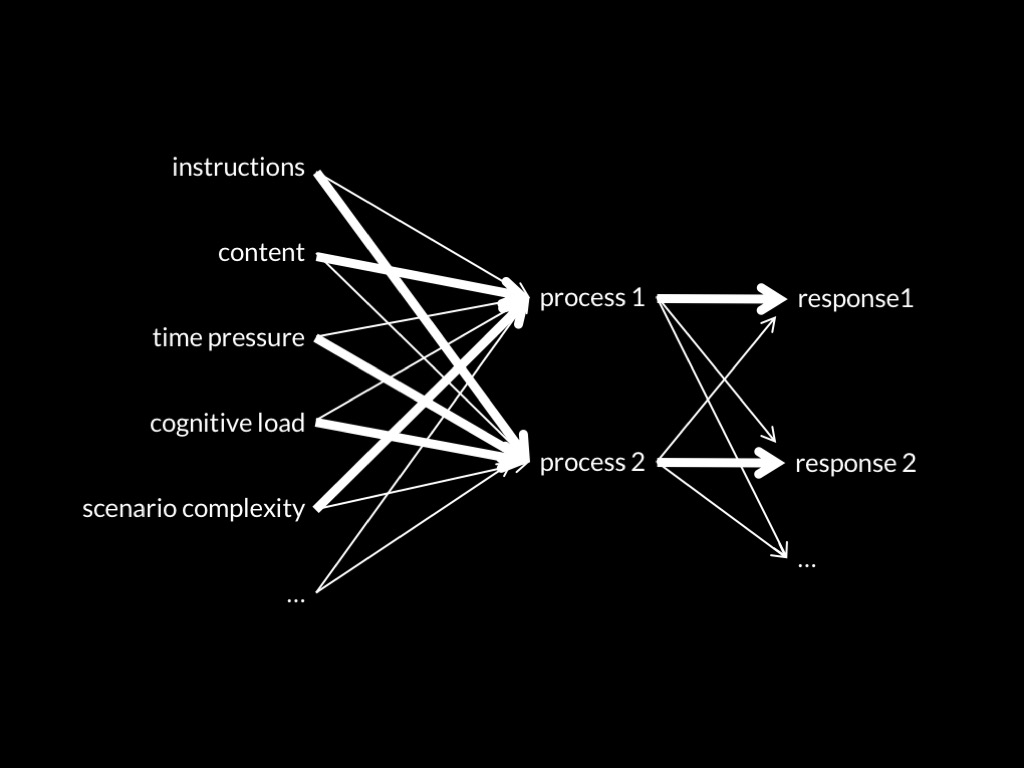

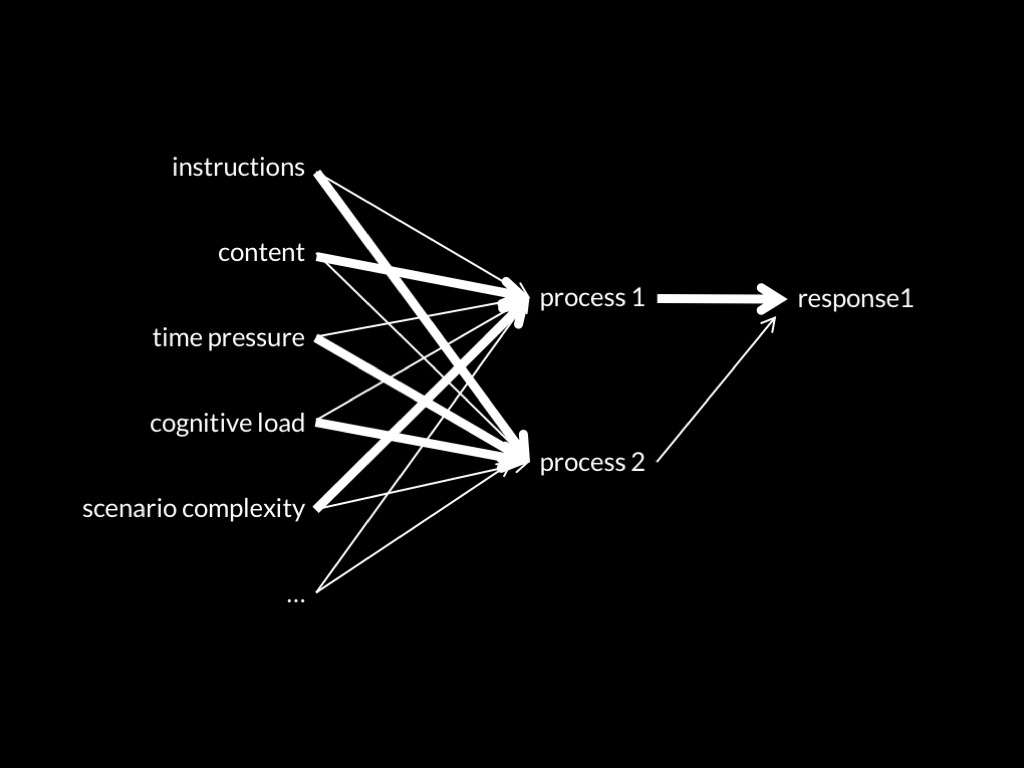

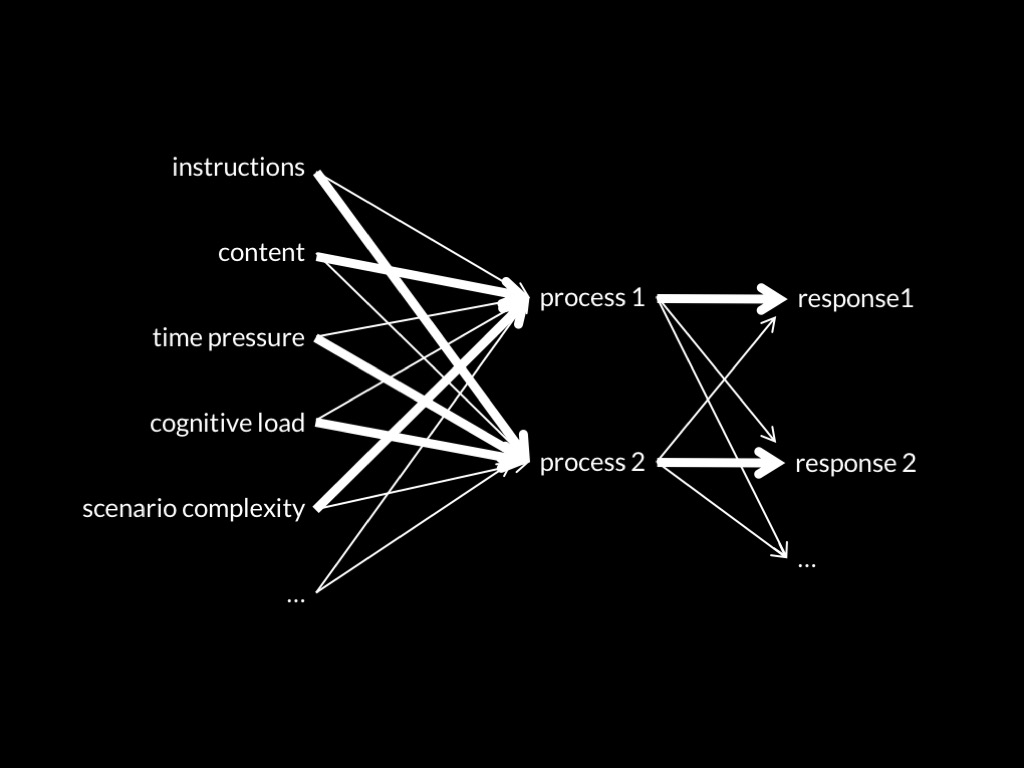

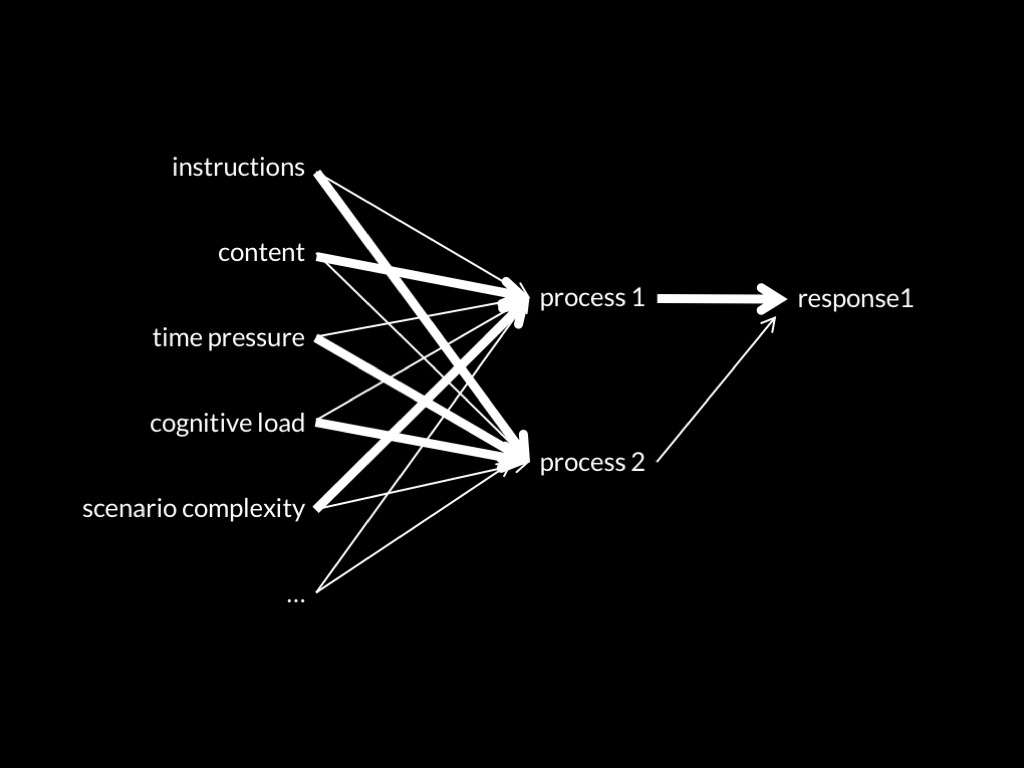

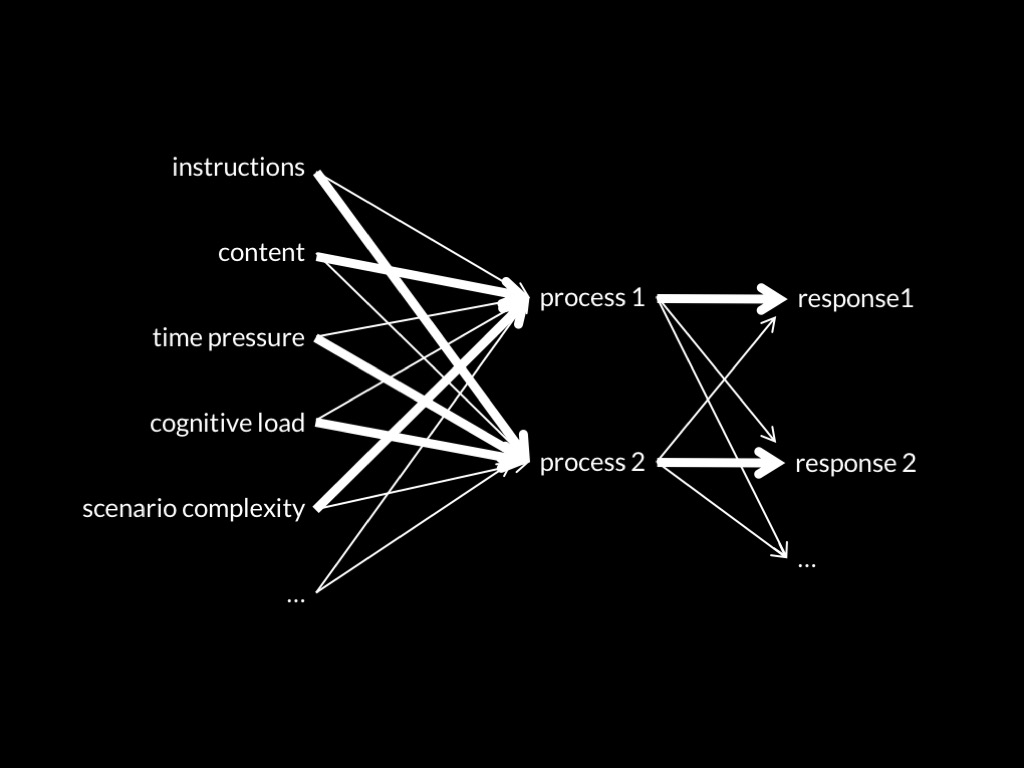

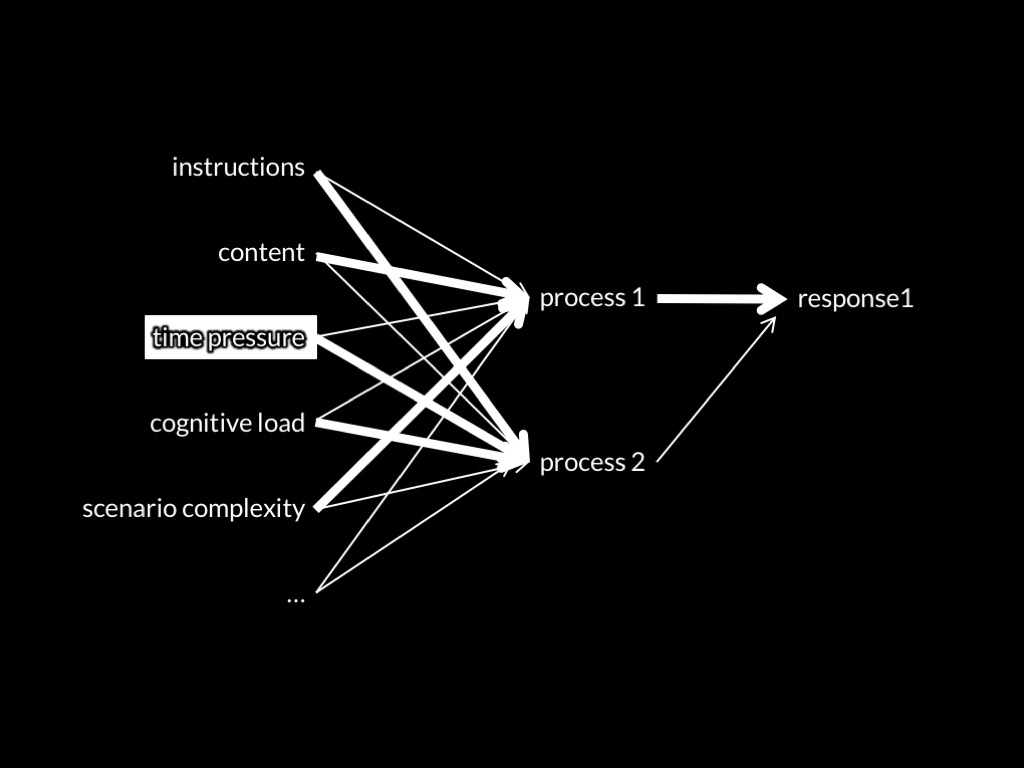

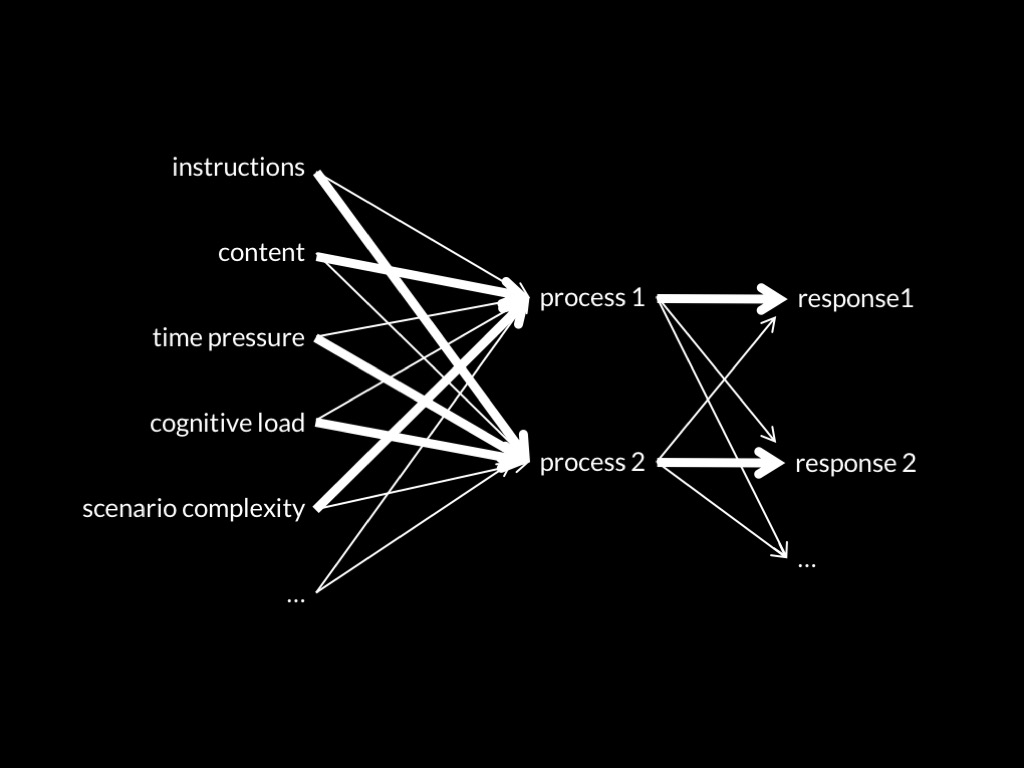

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

How to evaluate a study

1. Never trust a philosopher.

2. Is it really evidence?

a. Has the study featured in a review? If so, does the review broadly support the findings of this study?

b. Are there similar studies? If so, are the findings convergent?

c. Has the study been replicated?

How to evaluate a theory

1. Never trust a philosopher.

2. How good is the evidence?

a. Has the theory featured in a review? If so, does the review broadly support the theory’s main claims? ✓

b. Is there a variety of studies, from different labs, using different methods, which support the theory’s various predictions?

c. Are there studies which falsify the theory’s predictions?

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

aux. hypothesis: The slow process is responsible for characteristically consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

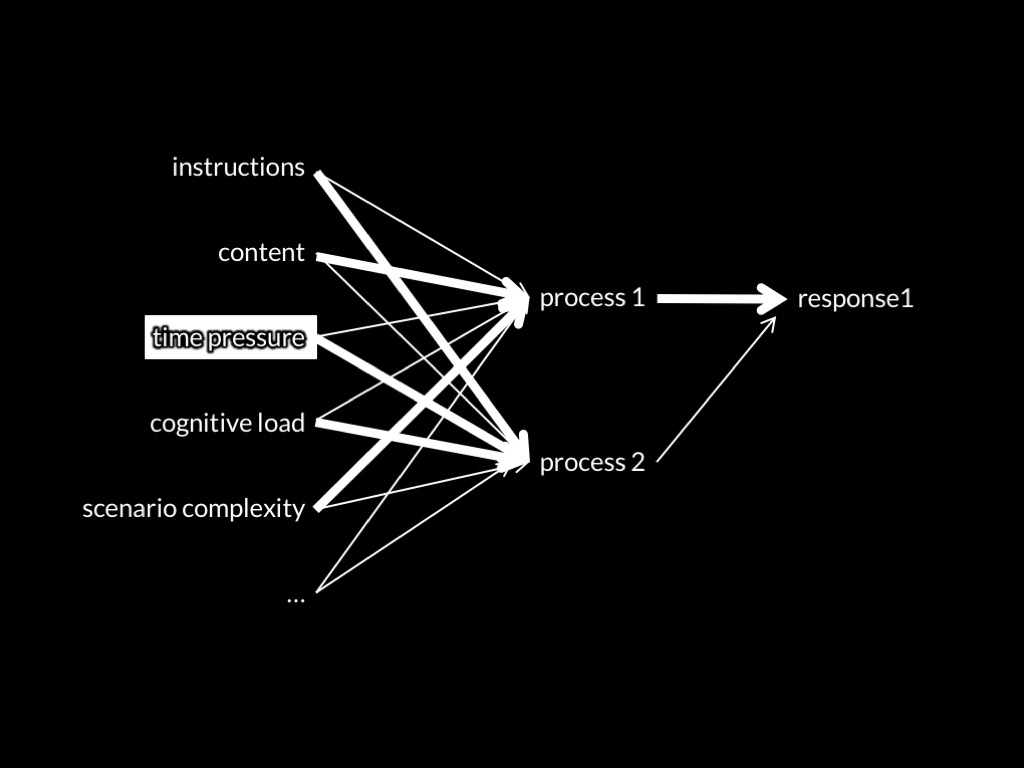

Prediction 1: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

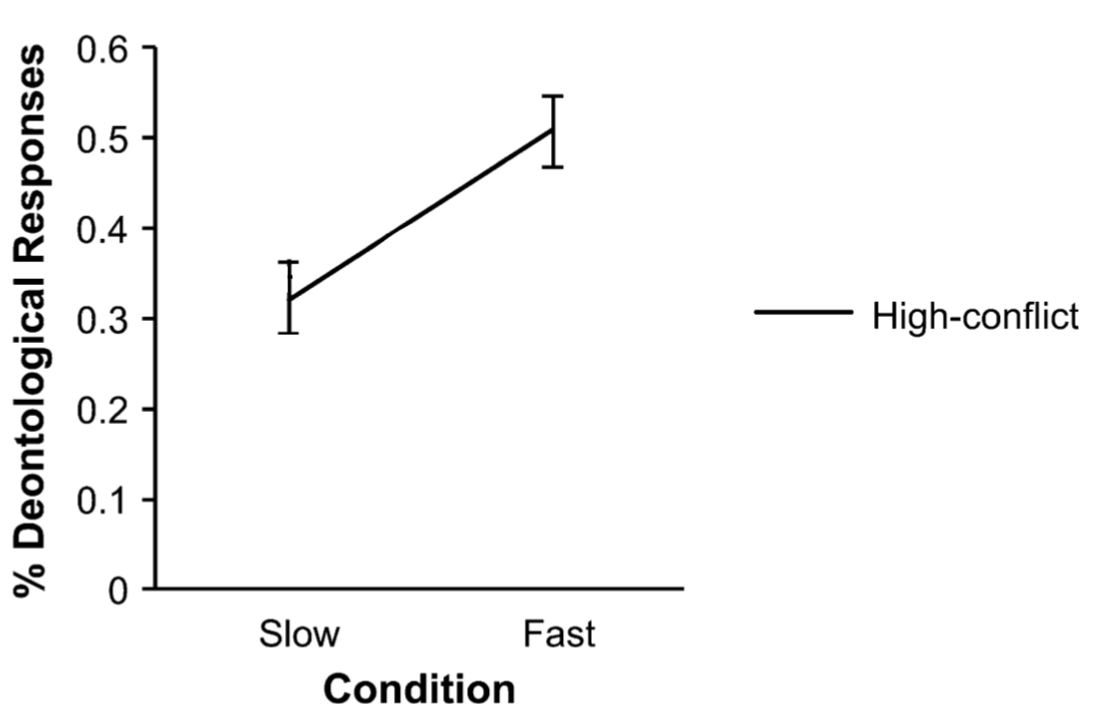

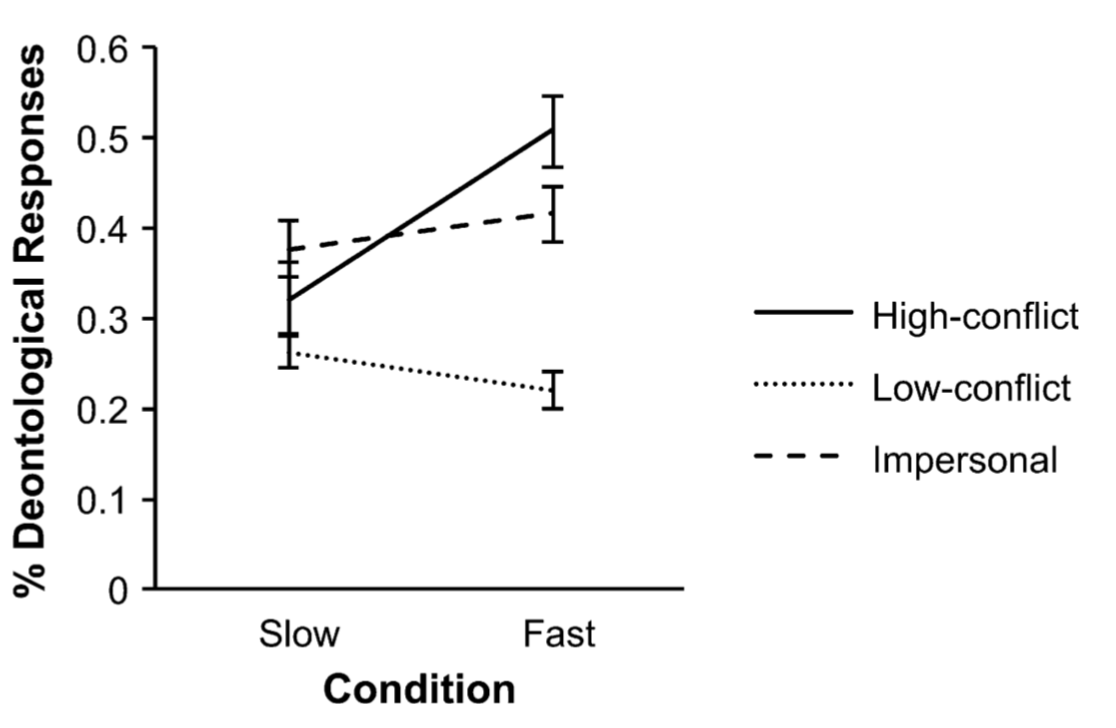

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 figure 1

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 figure 1

Suter & Hertwig, 2011 figure 1

‘participants in the time-pressure condition, relative to the no-time-pressure condition, were more likely to give ‘‘no’’ responses in high-conflict dilemmas’

Good start.

But are there other studies?

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

aux. hypothesis: The slow process is responsible for characteristically consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

Prediction 1: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

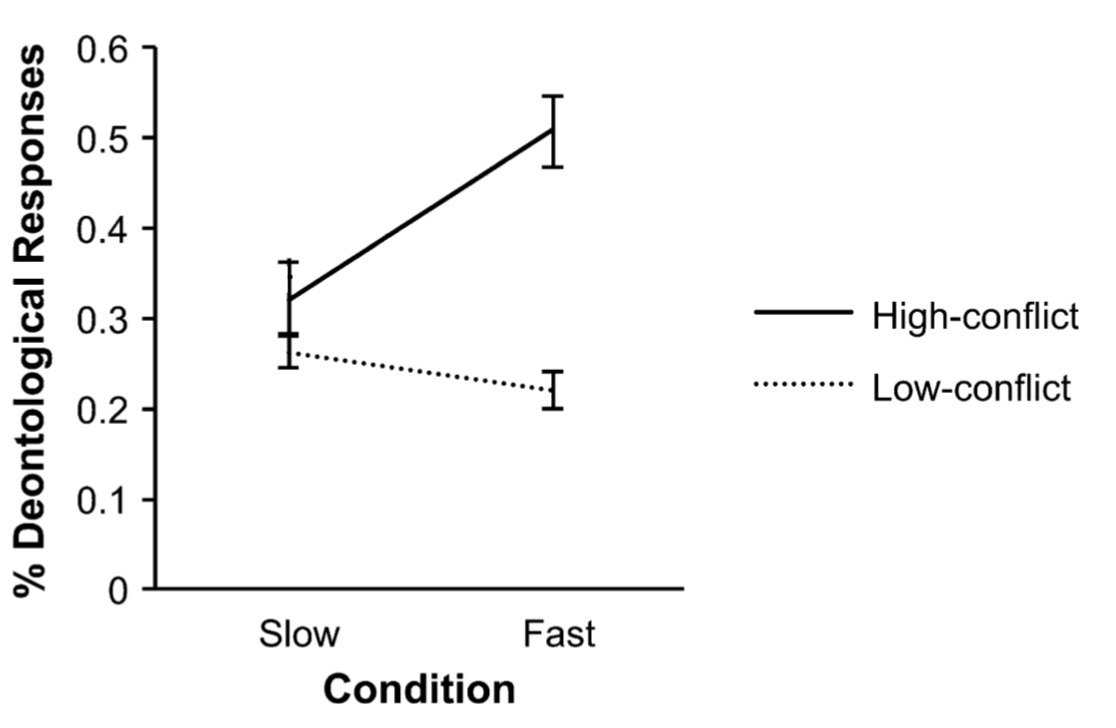

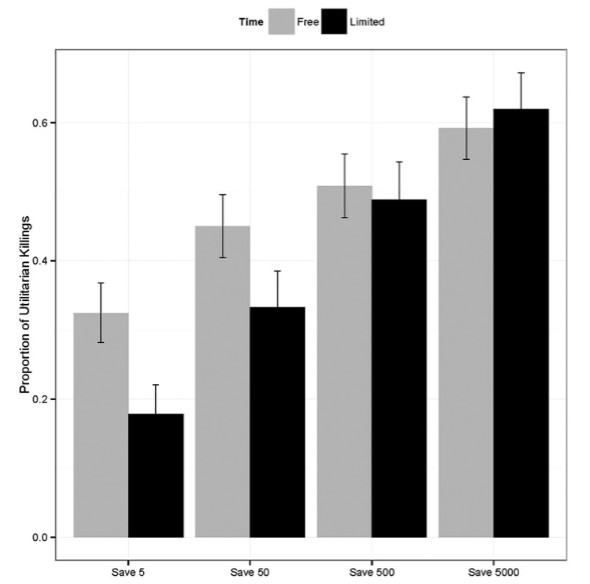

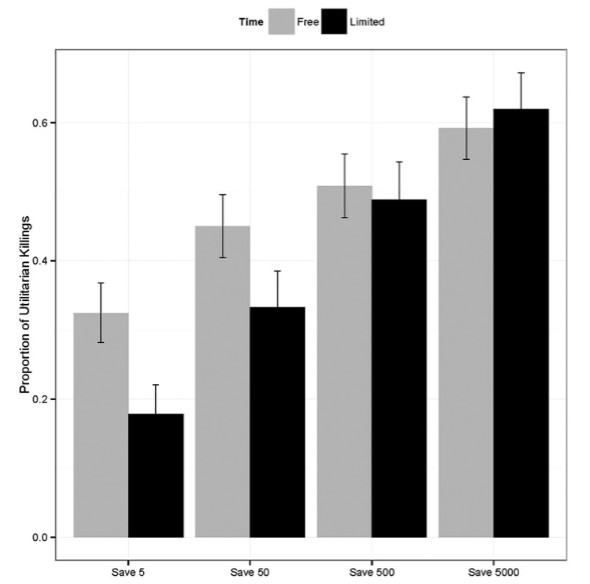

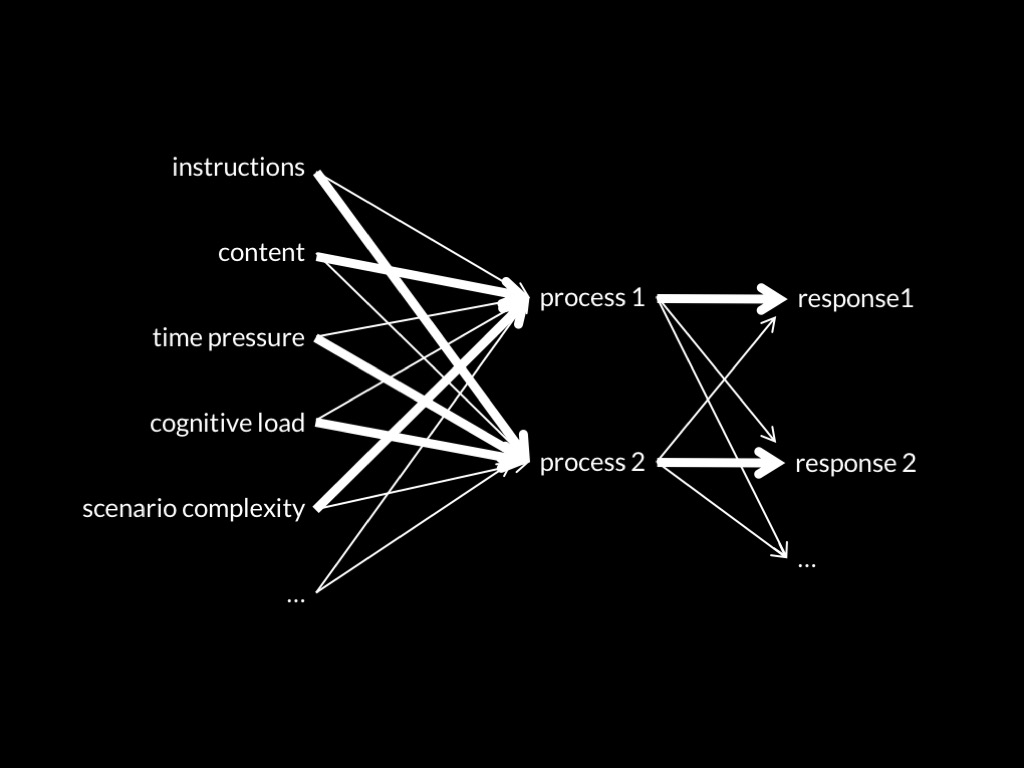

Trémolière and Bonnefon, 2014 figure 4

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

aux. hypothesis: The slow process is responsible for characteristically consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

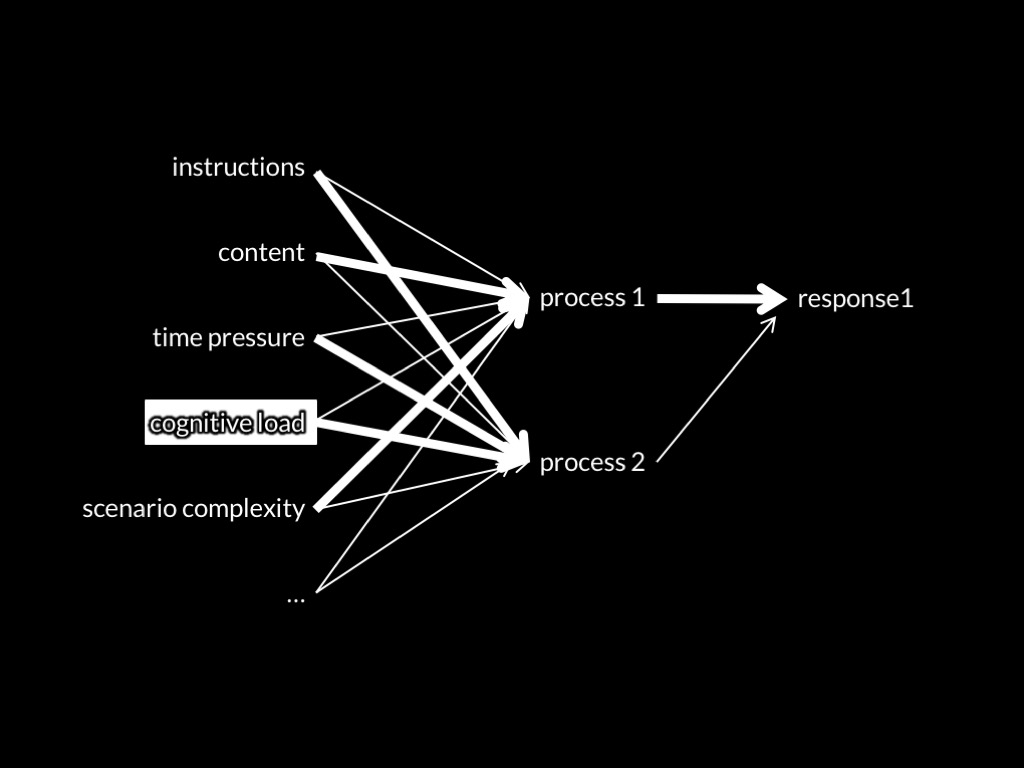

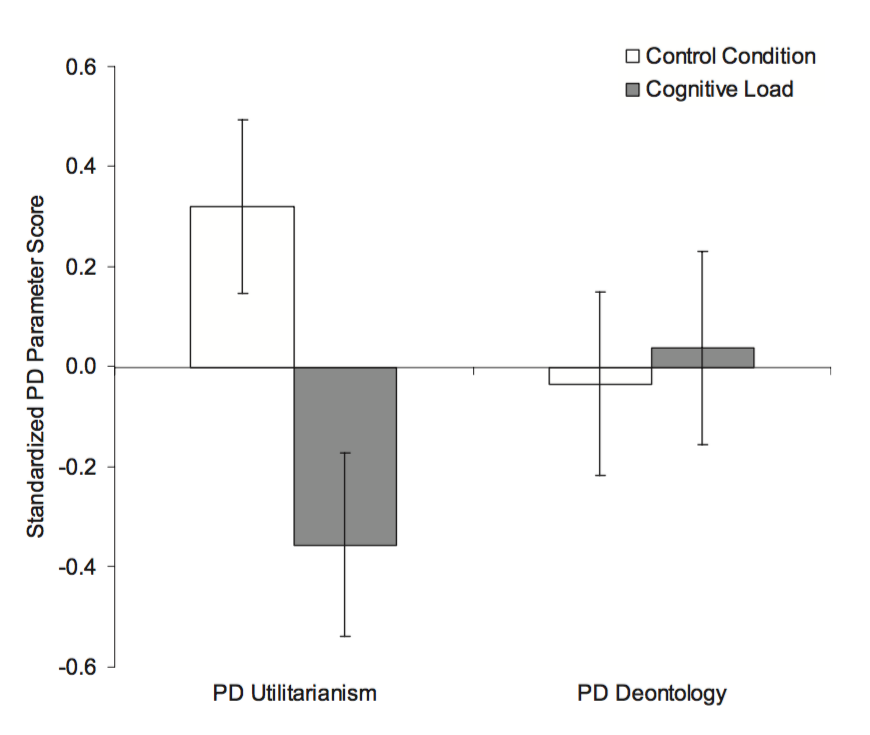

Prediction 3: higher cognitive load will reduce the dominance of the more outcome-sensitive process.

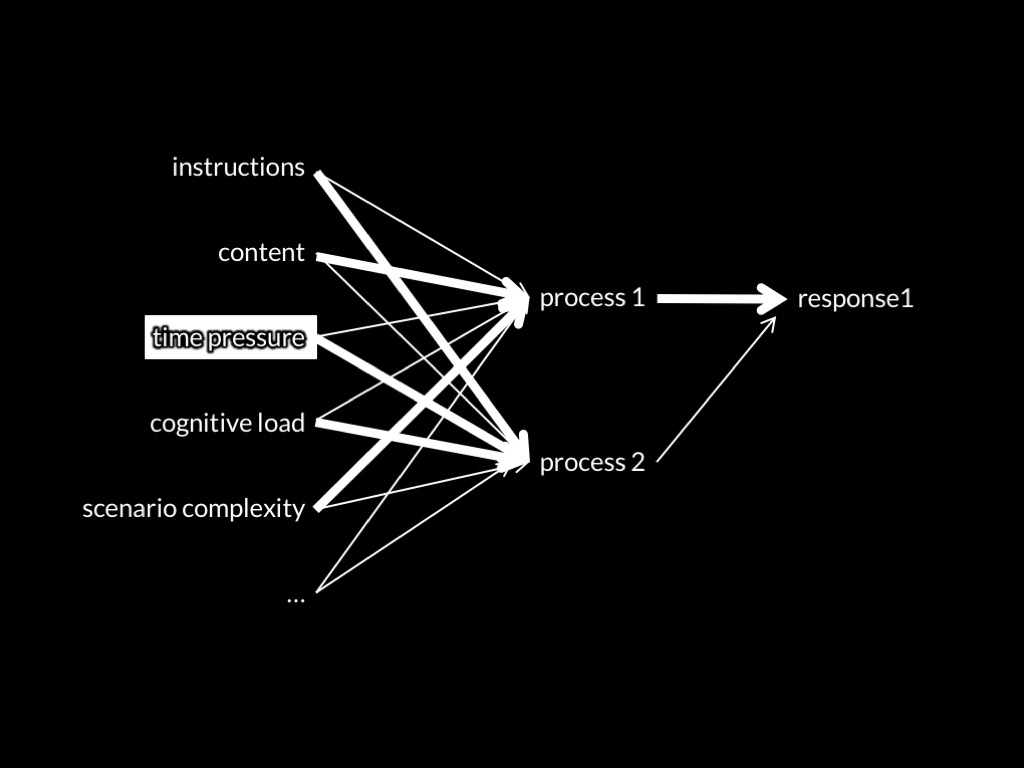

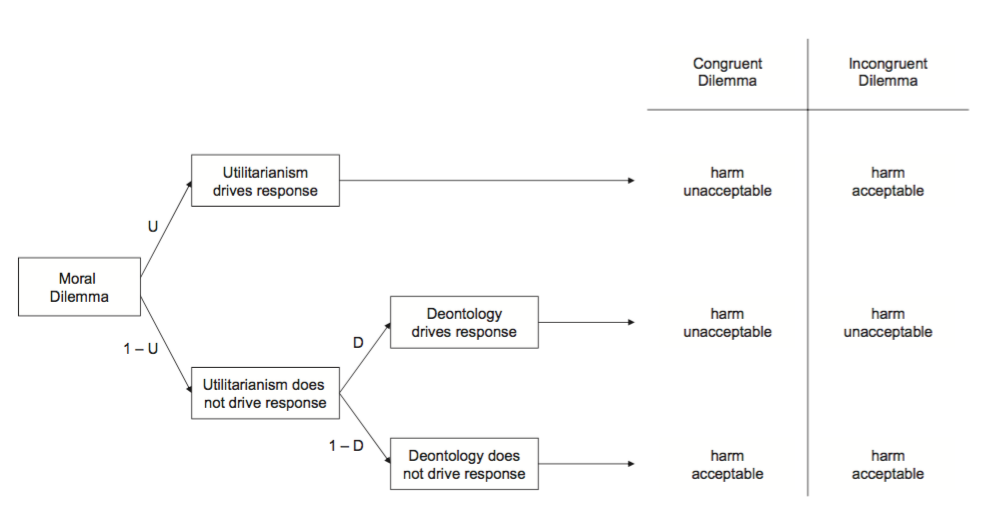

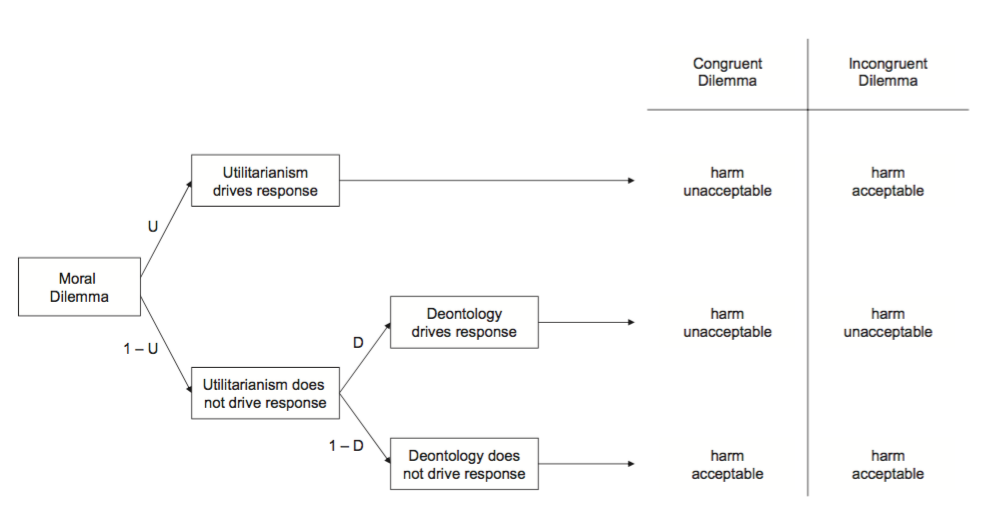

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 1

Conway & Gawronsky 2013, figure 3

Evidence Greene (2014) cites includes:

- Suter & Hertwig (2011)

- Trémolière & Bonnefon (2014)

- Conway & Gawronski (2013)

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. The moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

How to evaluate a theory

1. Never trust a philosopher.

2. How good is the evidence?

a. Has the theory featured in a review? If so, does the review broadly support the theory’s main claims? ✓

b. Is there a variety of studies, from different labs, using different methods, which support the theory’s various predictions? ✓

c. Are there studies which falsify the theory’s predictions?