Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Why Is the Affect Heuristic Significant?

preview of lecture: two puzzles

puzzle

Why do feelings of disgust sometimes influence moral intuitions?

(And why do we feel disgust in response to moral transgressions?)

puzzle

Why do patterns in moral intuitions reflect legal principles humans are typically unaware of?

start of lecture

moral psychology can distinguish

actual motivation

from

avowed motivation

pathogen

sexual

injury

(Tybur, Lieberman, & Griskevicius, 2009)

Pontzer (2021, p. Chapter 1)

illustration: gender and toilets

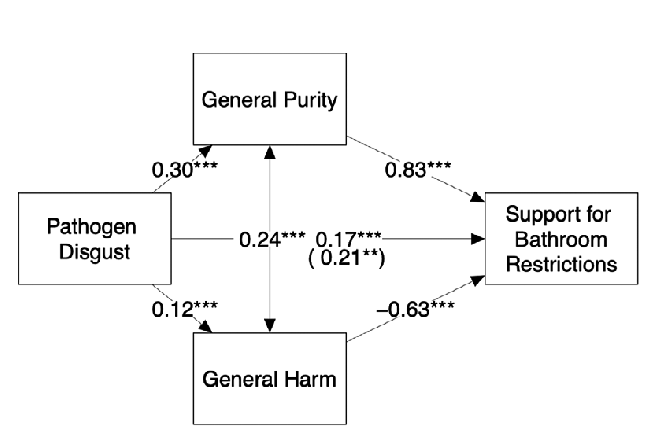

Which factors influence attitudes toward policies that limit the choice of toilet to an individual’s birth sex?

Method: measure each participant’s views on harm and sensitivty to pathogen disgust; to what extent do each of these factors predict the participants’ attitudes toward policies?

(Vanaman & Chapman, 2020)

How distguisting is ...

stepping in dog pooh?

seeing mold on some leftovers in your refrigerator?

finding a hair in your food?

0–6 [not at all–extremely distgusting]

(Tybur et al., 2009)

Vanaman & Chapman (2020, p. figure 3)

illustration: gender and toilets

Which factors influence attitudes toward policies that limit the choice of toilet to an individual’s birth sex?

Method: measure each participant’s views on harm and sensitivty to pathogen disgust; to what extent do each of these factors predict the participants’ attitudes toward policies?

Results: Your attitude towards policies that limit choice of toilet

is mainly a consequence of disgust (mediated by purity), not concern about harm.

Intervention: target disgust, not concerns about harm.

(Vanaman & Chapman, 2020)

moral psychology can distinguish

actual motivation

from

avowed motivation

the gap

‘the central phenomena are moral emotions and intuitions.’

(Haidt, 2008, p. 65)

Q2 What do humans compute that enables them to track moral attributes?

Q1 How, if at all, do emotions influence moral intutions?

Hypothesis 1

The ‘affect heuristic’:

‘if thinking about an act [...] makes you feel bad [...], then judge that it is morally wrong’.

What is a heuristic?

A heuristic links an inaccessible attribute to an accessible attribute such that, within a limited but useful range of situations, someone could track the inaccessible attribute by computing the accessible attribute.

‘We adopt the term accessibility to refer to the ease (or effort) with which particular mental contents come to mind.’

Kahneman & Frederick (2005, p. 271)

| device | What is tracked? (inaccessible) | What is computed? (accessible) |

| poison detector | toxicity | how encountering it makes me feel |

| moral intuition | right and wrong | how disgusted it makes me feel |

heuristics are a key feature of cognition

cannonical example

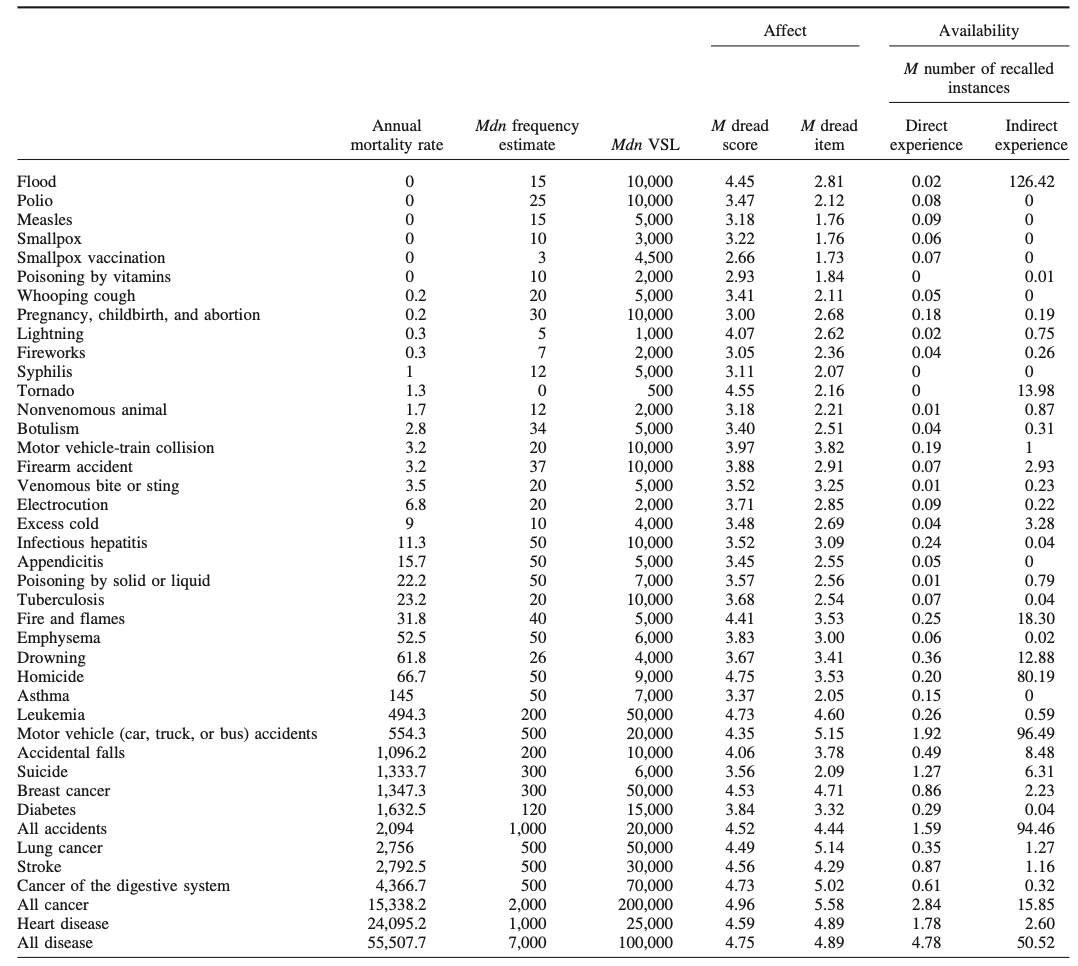

frequency and risk judgements

(Pachur, Hertwig, & Steinmann, 2012)

Pachur et al 2012, table 4

Judgements about whether an action a cancer is good or bad

- frequent in Switzerland

(which cause of death has a higher annual mortality rate?) - risky in Switzerland

(which cause of death represents a higher risk of dying from it?)

Note: the attributes to be tracked (frequency and risk) are inaccessible; and the correct answers are always identical.

Pachur et al. (2012)’s conjecture

Participants will use different heuristics for frequency and risk.

frequency

Availability Heuristic

The more easily you can bring cases of it to mind, the more frequent it is.

Prediction: frequency judgements will correlate with number of cases in social network.

risk

Affect Heuristic

The more dread you feel when imagining it, the more risky it is.

Prediction: risk judgements will correlate with own feelings of dread.

results: predictions broadly confirmed

compare methods: risk judgements vs ethical judgements

A heuristic links an inaccessible attribute to an accessible attribute such that, within a limited but useful range of situations, someone could track the inaccessible attribute by computing the accessible attribute.

Cost: accuracy (and therefore risk of bias)

Benefit: speed

heuristics are a key feature of cognition

‘the central phenomena are moral emotions and intuitions.’

(Haidt, 2008, p. 65)

Q2 What do humans compute that enables them to track moral attributes?

Q1 How, if at all, do emotions influence moral intutions?

With the heuristic model in hand, consequentialists can respond that the target attribute is having the best consequences, and any intuitions to the contrary result from substituting a heuristic attribute.’

(Sinnott-Armstrong, Young, & Cushman, 2010, p. 269).

Only by interpreting the activity of the emotive centers as a biological adaptation can the meaning of the canons be deciphered’ (Wilson, 1975, p. 563 quoted in Haidt, 2008, p. 68).

Hypothesis 1

The ‘affect heuristic’:

‘if thinking about an act [...] makes you feel bad [...], then judge that it is morally wrong’.

Implication 1: ‘if moral intuitions result from heuristics, [... philosophers] must stop claiming direct insight into moral properties’ (Sinnott-Armstrong et al., 2010, p. 268).

Implication 2: Should we trust moral intuitions? ‘Just as non-moral heuristics lack reliability in unusual situations, so do moral intuitions’ (Sinnott-Armstrong et al., 2010, p. 268)

illustration: gender and toilets

‘the central phenomena are moral emotions and intuitions.’

(Haidt, 2008, p. 65)

Q2 What do humans compute that enables them to track moral attributes?

Q1 How, if at all, do emotions influence moral intutions?

Only by interpreting the activity of the emotive centers as a biological adaptation can the meaning of the canons be deciphered’ (Wilson, 1975, p. 563 quoted in Haidt, 2008, p. 68).

Hypothesis 1

The ‘affect heuristic’:

‘if thinking about an act [...] makes you feel bad [...], then judge that it is morally wrong’.

Implication 2: Should we trust moral intuitions? ‘Just as non-moral heuristics lack reliability in unusual situations, so do moral intuitions’ (Sinnott-Armstrong et al., 2010, p. 268)

but is it true?